Assessing risks to Galapagos tortoises during rodent eradication

Penny Fisher is a member of Friends of Galapagos New Zealand and in 2011 took part in trials with the Galapagos National Park is assessing the risk to captive tortoises from bait intended for rats which predate on these giant reptiles. Here is her account of her participation in the trials and and also her close dealings with the giant tortoises which was not always to their liking!

Penny Fisher is a member of Friends of Galapagos New Zealand and in 2011 took part in trials with the Galapagos National Park is assessing the risk to captive tortoises from bait intended for rats which predate on these giant reptiles. Here is her account of her participation in the trials and and also her close dealings with the giant tortoises which was not always to their liking!

Penny Fisher, Wildlife Ecology and Management team, Landcare Research

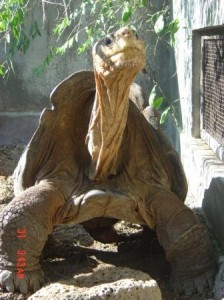

Complete removal of invasive rodents (rats and mice) from islands around the world have seen some dramatic improvements in biodiversity, and significant benefits for endemic fauna and flora are expected if rodents can be permanently eradicated from islands in the Galápagos. The iconic giant Galápagos tortoises are no exception – even such large, long-lived creatures are impacted by rodents as tortoise eggs and hatchlings are consumed by rats.

Successful rodent eradications from islands have often been achieved using aerial application of cereal pellet bait containing an anticoagulant rodenticide. Using this method, the Galápagos National Park is undertaking a staged approach to eradication of introduced rodents from islands in the Galápagos. The most recent phase was completed in 2012 and included the island of Pinzon, which has a wild population of tortoises (Chelonoidis ephyppium).

Because very little was known about the toxicity of the rodenticide to tortoises and reptiles in general, it was essential to assess the potential risk that aerial application of the toxic bait posed to tortoises, so some research in this area formed part of planning rodent eradication from Galápagos tortoise habitat. Working with the National Park and Island Conservation (a charitable organization www.islandconservation.org/ ) I visited the Galápagos in early 2011 to help with trials with captive tortoises.

A few individuals showed interest in eating the cereal pellet baits but the majority preferred their normal plant diet. This suggested that bait uptake by tortoises in field conditions would likely be low when natural food was readily available. But because some tortoises would ingest bait, we also tested their blood to indicate whether this was likely to produce any adverse effect. Blood samples were taken before and after the tortoises ate known amounts of the rodenticide – neither the tortoises nor I found this process much fun, although I did my best to make it up to them afterwards with bribes of papaya and melon! An automated coagulometer was used to test for blood clotting times, where increased time would indicate reduced ability of the blood to coagulate (a typical toxic effect of this rodenticide in mammals and birds).

No significant changes in blood coagulation were measured over a two week period following ingestion of the rodenticide by tortoises. Interestingly, tortoises appeared to have higher normal blood coagulation times than those measured in mammals, supporting the idea that in comparison to mammals tortoises have a relatively low susceptibility to anticoagulant toxicity. In the context of the aerial bait application rates to be used ine rodent eradication, the risk assessment suggested that tortoises weighing more than 20 kg would be unlikely to encounter and consume enough bait pellets to have a harmful effect.

susceptibility to anticoagulant toxicity. In the context of the aerial bait application rates to be used ine rodent eradication, the risk assessment suggested that tortoises weighing more than 20 kg would be unlikely to encounter and consume enough bait pellets to have a harmful effect.

To date the removal of rats from Pinzon appears to have been successful although the island is still being checked regularly for any sign of surviving rats, with a two year ‘all clear’ being the signal to declare the eradication has been achieved. More detailed information about the history, progress and future plans for rodent eradications in the Galápagos was recently summarized by Henry Nicholls in a news article for Nature 497 (7449): 306-308.

http://www.nature.com/news/invasive-species-the-18-km2-rat-trap-1.12992